Welcome to Gateways, where you experience the Nevi'im—the Prophets—through the teachings of Don Yitzchak Abarbanel, distilled into easy-to-follow lessons.

So far, we’ve been exploring Abarbanel’s introduction to the book of Isaiah. If you missed it, go back to the homepage and check them out.

In today’s lesson, we’ll cover the opening of the book of Isaiah. The entire prophecy—which Abarbanel divides into five parts based on the divisions of the text—is read as the Haftarah for Parshat Devarim, which falls on the Shabbat before the 9th of Av. That Shabbat is known as Shabbat Chazon, named after the opening word of this prophecy. It marks a moment of poignant regret, as we recall our sins—how far we’ve fallen—and how much God trusts that we will once again succeed.

In this lesson, we’ll focus on the first of the five sections. By the end, you’ll have a deeper appreciation for the importance of this stinging rebuke and it’s lessons for us today.

I’ll include Abarbanel’s overview, the verses, his questions, and his answers. I’ll conclude with a short takeaway of my own. I hope you’ll share yours.

For an unabridged version, click here. My additions here are in italics. I've used bold to highlight key ideas and make the content easier to follow.

Jeff

Photo by Jnt Airdrop

Overview

The general intent in this prophecy is to rebuke the people of Judah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem for the wickedness of their actions and for being ungrateful before Him, may He be blessed, and to warn them to accept His rebuke and return to God, so that exile and destruction — which came upon the Ten Tribes — will not come upon them.

And together with this, to foretell to them the troubles that will happen in the days of Ahaz, and the comforts and good things that will be in the days of his son Hezekiah, as will be explained in the commentary on the verses.

This section presents two arguements:

The Jewish people should recognize God. If an ox or donkey realizes where their food comes from, so should the Jewish people.

The destruction surrounding the kingdom of Judah and Jerusalem is a sign of God’s displeasure. They should get the message now before it is too late.

In our contemporary, post-prophecy age, we typically don’t look at surrounding events and say, “Look, God’s upset with us, that’s why this is happening” for a very simple reason, we aren’t prophets. God hasn’t directly told us. And yet, we know that God is involved the running of world affairs, and has a message for us, as I’ll talk about later in this lesson.

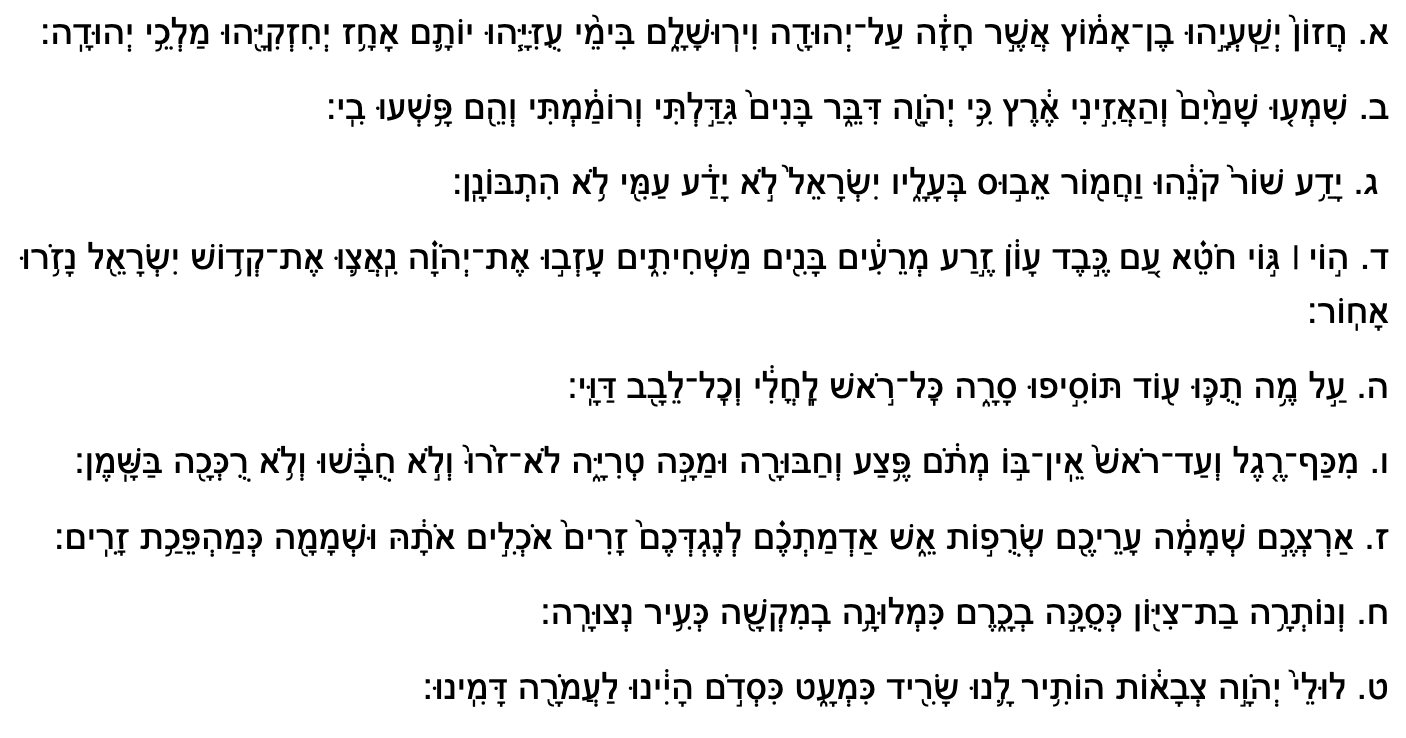

Verses

1. The vision of Isaiah son of Amoz, who had vision-prophecy concerning Judah and Jerusalem in the reigns of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah.

Questions

Abarbanel identifies four questions that relate to this first section.

The first question:

Why was this prophecy placed at the beginning of the book—if in fact the first prophecy that Isaiah saw was in the year King Uzziah died, as it says: Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? And I said: Here I am, send me! (Isaiah 6:8).

So, it would have made sense for that prophecy to be placed at the beginning of the book.

The second question:

About the phrase: The vision of Isaiah son of Amoz.

If this statement refers to all the prophecies in the book—as the plain reading seems to suggest—then why is the word vision (חזון) used in the singular? It should have said visions of Isaiah, or like it says “The words of Jeremiah”?

The third question:

Why did Isaiah choose to begin his book with such a harsh rebuke and severe vision against Israel? It would not have been appropriate for his very first words to be so strong.

Our teacher Moses, for example—in Egypt and at Mount Sinai, at the beginning of his prophecy—spoke to Israel in a conciliatory way. Only at the end of his words, in Parashat Haazinu, did he offer a rebuke similar to the one we see here.

The fourth question:

Why does it say “which he saw about Judah and Jerusalem”—as if his prophecies were only about the people of Judah and the inhabitants of Jerusalem? But that’s not true.

Isaiah also prophesied about the kingdom of Israel many times. Even in this first prophecy, he speaks about the kingdom of Israel when he says: “Israel does not know; My people do not understand.”

Answers

The Abarbanel answers by giving a mini-essay, giving us the information needed to answer the questions. We’ll sum it up, but first let’s see what he has to say.

“The vision of Isaiah son of Amotz…”

The phrase “The vision of Isaiah son of Amotz” refers only to this first prophecy—meaning: the prophecy that came to him about that particular subject.

That’s why it says vision (ḥazon) in the singular—because it is just one prophecy.

And so, the phrase “which he saw about Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzziah, Jotham…” is not to be read as connected directly to the word ḥazon,

Rather, its meaning is: After saying “The vision of Isaiah son of Amotz” about this prophecy, the verse clarifies the general time when Isaiah prophesied—namely, “which he saw about Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzziah, Jotham…”

It also informs us that this prophecy was of a clear and elevated level, called a ḥazon (vision), as I explained in the introduction to the book.

The verse also says Isaiah was the son of Amotz to tell us two high qualities he had:

His lineage and the honor of his family, that he was from royal descent—because Amotz and Amaziah king of Judah were brothers, as I mentioned in the introduction.

That prophecy was an inheritance to him, a legacy passed down from his ancestors—just as the Midrash (Vayikra Rabbah 6:6) says he was a prophet, the son of a prophet, and that’s why he is associated with his father.

So the verse comes to teach us that since Isaiah was from the royal line and inherited prophecy from birth and the womb, he had the strength to rebuke his people harshly and severely for the honor of God.

And perhaps the verse is hinting at a deeper divine idea: that Isaiah saw this same prophecy during the reign of Uzziah, and then again during the reign of Jotham, and again in the days of Ahaz, and again in the days of Hezekiah—a total of four times.

It’s as if Isaiah were a voice calling out: “Clear the path of the Lord” during the reign of each of those kings—constantly informing them of the coming destruction of Samaria and the exile of the tribes of Israel.

So then, this prophecy was one single prophecy, and that’s why it’s called ḥazon in the singular.

And it was about Judah and Jerusalem, because even though it mentions the kingdom of Israel, the main warning and rebuke was directed at Judah and Jerusalem.

And perhaps this was in fact the first prophecy that Isaiah saw during the reign of Uzziah. Then later, in the year Uzziah died—or when he became a leper, as the Targum explains—he saw the vision mentioned there, where God says: “Whom shall I send?”

But that vision was not the beginning of Isaiah’s prophecy—it was due to the weight and seriousness of that particular mission, for which no one else was worthy.

And this prophecy, full of rebuke, was placed at the beginning of the book—either because it was the first in time, or because of its elevated status in having been repeated so many times during the reigns of these kings.

And through the explanation I’ve provided for these verses, the first, second, third, and fourth questions that I raised earlier have been resolved—as you can see from the content.

In summary:

Question 1: why does this prophecy come first?

Answer: Either because it actually came first, or because of it’s importance since it was repeated so many times.

Question 2: why is it referred to in the singular, if he prophesied at all these different times?

Answer: It was one prophecy.

Question 3: why does Isaiah start with such harsh rebuke?

Answer: He was a descendant of a prophet, from the royal family, and had the strength to rebuke the people.

Question 4: why does the verse open saying it was about Judah and Jerusalem, when in fact the kingdom of Israel is also mentioned?

Answer: the kingdom of Israel is mentioned as a warning to what will happen to Judah and Jerusalem if they don’t repent.

Gateways is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Takeaways

There are a few ideas that come to mind:

Isaiah used his station—as part of the royal family—to speak truth to power.

He repeated this prophecy multiple times. He never gave up hope that people might one day listen.

Isaiah is calling us, now, to pay attention to what is happening, to see the hand of God in everything, and simply pay attention.

Rav Avraham Yischak HaKohen Kook, Z’L, writes in his sefer Orot, and I’ll lightly paraphrase here:

…(we are called) to see the world through the miracles and nature, which become one through those with pure comprehension, who see with confidence and total revelation the hand of God of Israel in all the changing times… as has been from the beginning.

“Before the mountains were born, before You brought forth the earth and the world, from eternity to eternity, You are God. You turn mortals back into dust, saying, “Return, you children of men” (Psalms 90:2-3).

Nature is never abandoned in her path, history is not a widow… in her life a powerful redeemer, the Rock of Israel and its redeemer, the God of Hosts is His name.

I’m writing this on day 675 of our hostages still being held in the tunnels of Hamas. I’m so deeply worried about what the future of the Israeli conquest of Gaza will mean for our beautiful, sacred, holy young men.

And yet, I can’t forget the unbelievable 12-day miracle that saw Iran crippled. And so, I hear Isaiah’s message: look at the world around you. What is God trying to tell us? And I hear Rav Kook reminding me, reminding us, that history is not a widow.

God is alive and bringing the world, through His circuitous routes, to its redemption.